Oundle in the Eighteenth Century

A talk given to the British Legion – Women’s Section on 28th July 1998.

by Julia Moss

One of my reasons for choosing to look at Oundle in the 18th century is the survival of a series of day books or diaries kept by John Clifton, who was a master carpenter in Oundle in the second half of the 18th century. John Clifton was born in 1728 and the day books cover the years 1763 to 1784, the year of his death. He was not only a master craftsman but a man of wide interests, ranging from astronomy to gardening - he also took a lively interest in the gossip of the day. Alice Osborne, I'm sure lots of you know, transcribed these diaries for the National Record Office and in 1994 she and David Parker produced a fascinating book based on Clifton's diaries. The book and the diaries themselves deserve to be more widely known and much of what I shall be saying is based on this source.

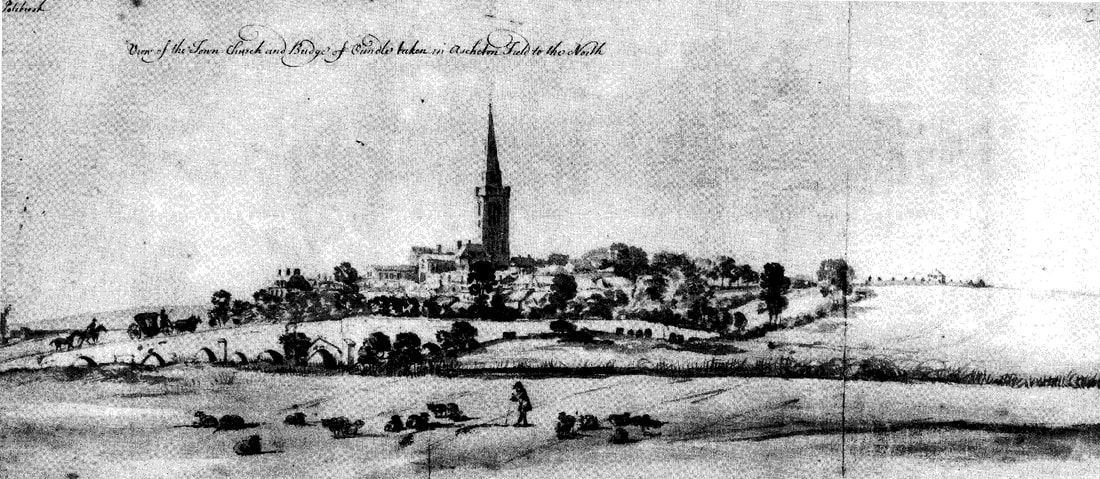

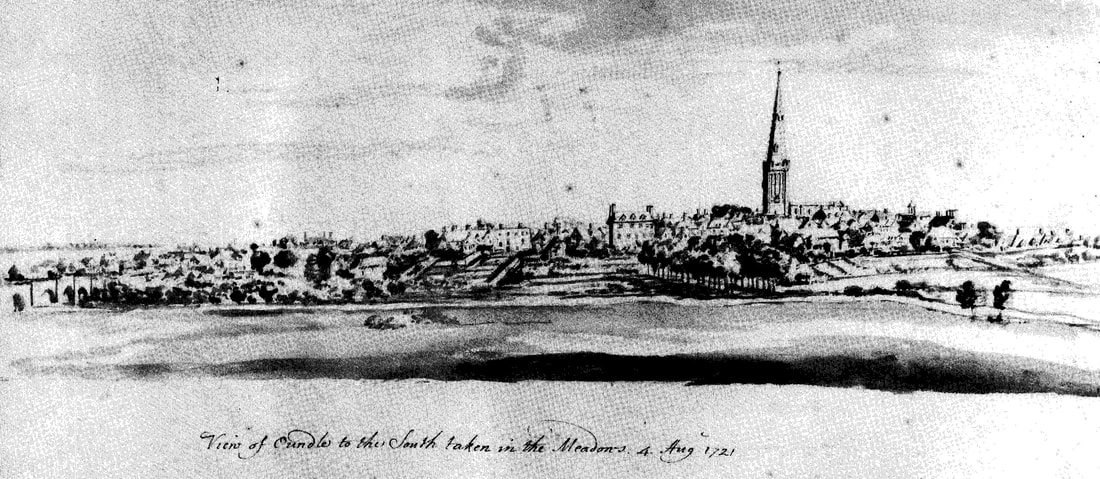

However, I want to begin by setting the scene with a few basic facts about the town itself in the early 18th century. Well, although we haven't any maps showing the layout of the Oundle town centre or any census figures for the population, we know quite a lot about the town from the County history compiled by John Bridges around 1720. Bridges visited Oundle in 1719 and 1721 and wrote “Oundle on the east and north is bounded by the Nyne which takes in a common field called St, Sythes. On the west Benefield and Stoke and on the north Glaphorn. Here are about 350 families”. If we take the average household size of between four and five, we will get a population of about 1600 people. This seems quite possible as by 1801, the date of the first census, there were 2068 people living in Oundle. This is about half of the present population, but these people were almost all crammed into the areas we think of as the town centre, surrounded by open and enclosed fields. Bridges goes on to describe the town of the 1720s. As well as these written accounts we have two beautiful views of Oundle, drawn by the Dutchman Peter Tillemans to accompany Bridges’ account.

A talk given to the British Legion – Women’s Section on 28th July 1998.

by Julia Moss

One of my reasons for choosing to look at Oundle in the 18th century is the survival of a series of day books or diaries kept by John Clifton, who was a master carpenter in Oundle in the second half of the 18th century. John Clifton was born in 1728 and the day books cover the years 1763 to 1784, the year of his death. He was not only a master craftsman but a man of wide interests, ranging from astronomy to gardening - he also took a lively interest in the gossip of the day. Alice Osborne, I'm sure lots of you know, transcribed these diaries for the National Record Office and in 1994 she and David Parker produced a fascinating book based on Clifton's diaries. The book and the diaries themselves deserve to be more widely known and much of what I shall be saying is based on this source.

However, I want to begin by setting the scene with a few basic facts about the town itself in the early 18th century. Well, although we haven't any maps showing the layout of the Oundle town centre or any census figures for the population, we know quite a lot about the town from the County history compiled by John Bridges around 1720. Bridges visited Oundle in 1719 and 1721 and wrote “Oundle on the east and north is bounded by the Nyne which takes in a common field called St, Sythes. On the west Benefield and Stoke and on the north Glaphorn. Here are about 350 families”. If we take the average household size of between four and five, we will get a population of about 1600 people. This seems quite possible as by 1801, the date of the first census, there were 2068 people living in Oundle. This is about half of the present population, but these people were almost all crammed into the areas we think of as the town centre, surrounded by open and enclosed fields. Bridges goes on to describe the town of the 1720s. As well as these written accounts we have two beautiful views of Oundle, drawn by the Dutchman Peter Tillemans to accompany Bridges’ account.

The town of Oundle which John Clifton knew was therefore what we call the town centre. The area in which I live, called St. Peters Road, formed part of the three great open fields, Hill Field, Howhill Field and St. Sythe’s Field - often a fourth field, Pixley Field is listed.

The usual crops were wheat, peas and beans, and barley, and every third or fourth year a field would be kept fallow to rest it. The drawing shows sheep down on the meadows, still a familiar sight from Barnwell bridge. As the fields were farmed in common, there could be no farmhouses in the fields- the land was farmed from the town and John Clifton makes frequent reference to agricultural matters, for instance, in 1778 he wrote that “St Sythe’s Field and Pexley Field were wheat that year”. Pixley Field lay around Benefield Road, near the Golf Club and some of it is still agricultural land. Much of St. Sythe’s Field is occupied by the buildings and playing field of Prince William school.

On 22nd of August Clifton wrote “A very hot day - Mr. Chatteris’s harvest cart tonight. Old Tom Hawthorn’s harvest cart tonight. These are the first this year”. In those days harvest generally seems to have been later - probably the varieties of wheat used took longer to ripen. Crops were brought back from the fields in the harvest carts and stored in the backyards of the farmers’ houses in town - some of the grand houses like Cobthorn and The Berrystead had substantial stone barns which are still standing. For the farmers in West Street access to their backyards would have been from South Road and Milton Road, known as South Backside and North Backside respectively. Oundle’s first map or street plan, made in the early 19th century when the open fields were enclosed, shows the layout of the town with the long narrow strips behind the houses and gives the contemporary names such as Chapel End.

The getting in of the harvest was celebrated in the usual way. John Clifton's entry for 25th of August 1778 records “A glorious fine harvest day… Mrs Palmer’s Harvest Cart tonight and the fellows all drunk”. Harvest beer was apparently stronger the normal beer!

It's likely that most of these Oundle farmers were not just farmers, they probably had another occupation as well. The militia list of the previous year,1777, shows a few farmers and graziers but there were” innholders”, butchers, bakers, shoemakers, gardeners, wheelwrights and a fellmonger, as well as a man in more unusual occupation such as hairdresser, and the basket maker. Some at least of these must hold farmland in the open fields. Oundle formed part of the Manor of Biggin and the manorial court rolls contain much valuable information about property holding in the town. The militia list gives the occupation of a number of men as servants but few if any would have been indoor servants, such as footman, most of them would have been farm servants, or agricultural labourers.

Market towns like Oundle also provided a wide range of services to the surrounding villages, themselves agricultural settlements.

Although the street- plan of the town centre has changed little and some of the buildings such as the parish Church, Cobthorn, Bramston, The Berrystead, and even the Mill Lane cottages, remain externally much as they were in the 18th century, there have been important changes in the town's overall appearance, particularly in the marketplace. Some of you will be familiar with Shilibeer’s prints of the marketplace before the improvement act of 1825 and after. The improvements swept away the Butter Cross and the higgledy-piggledy collection of buildings known as Butcher’s Row and replaced them with the Market Hall. These prints present a much less tidy and orderly town centre and they also show clearly the cobbles and the lack of pavements.

In Clifton's day Oundle school was a small Grammar School and the school buildings, which now dominate the upper end of New Street, were not yet built in the early 18th century the only school building was the old guild hall, both almshouse and school room, which was replaced in the 1850s by Laxton Long Room.

The first of the school’s “new” buildings was the schoolmaster's house in 1763, which was built by Martin Cole of Peterborough, and entries in the day books suggest that John Clifton may have undertaken some of the carpentry. Houses which now form part of Oundle school such as Cobthorn, Bramston and the old water board were all privately owned, and John Clifton frequently refers to work which he undertook for the owners. For instance, on December 15th1766 he writes “Myself at Mr. Bramston's sash and blinds to the street parlour windows all day” and a few days later “Myself in the morning and till 2 o'clock hanging a Bell in Mr Bramston's nursery, then at Mr Johnston's houses taking an account of the stuff”.

He and his assistants were also involved in making coffins, sadly often for children, and in making furniture for various customers. He did a lot of work for Mr Burton who lived at Queen Anne’s. For example, in January 1772 he writes “Richard all day in the shop finishing Mr Burton's Oak table and beginning a mahogany 2 leaf Ditto for him”. The following years there were various entries relating to Mr Burton's bookcase “Richard at the cornice and frame to Mr Burton's bookcase”, entries like this and the codicil to John Clifton's own will listing all his possessions, give some idea of the household possessions of the day.

Alice Osborne did a great deal of work on the Oundle buildings of the time and she came to the conclusion, from entries in the day books and elsewhere, that John Clifton owned a number of properties in the town. She thinks he may have lived in Mill Lane as a boy, but as an adult he lived in West Street in a building part of which was occupied by one of Oundle's numerous pubs, the Green Man. In August 1778 he writes “The new sign post fixed by Mr Ashley's door today and the new sign of the “Green Man” hung in the frame on top of it”. In more recent times Mr Wade had a butcher’s shop in part of the building.

As I mentioned earlier John Clifton was a man of wide interest, who took a very active part in the life of the town, but there is one important aspect of life about which he had nothing to say - family life. He remained a bachelor and his view of his fellow townsmens’ marital affairs was often, though not invariably, rather cynical. In January 1779 he wrote “This morning my old neighbour nanny Eaton was married at our church to a young man of Geddington named Brown. Better late than never”.

There are many references to the parish church in Clifton's day books, relating mainly to the fabric rather than to the more spiritual aspects of the church life. In June 1766 he wrote ”Myself and William the church all day at the first bay of roofing at the South aisle with new beam, etc.” In January the following year he wrote “Myself at the church on the leads and at the bells. Shovelling snow away”. My impression is that the winters were colder than they are now. For instance, on the 14th of January 1768 he wrote “Tonight they broke the ice at Barnwell Bridge it having been a severe frost and deep snow ever since two days before Christmas”.

As a carpenter John Clifton was frequently employed in making coffins and it has been suggested he may have become Sexton after the death in 1772 of John Glasborow who had held the post for over 30 years. A very sad entry for 6th September 1776 reads “A little child of Mr Bishop's supervisor buried tonight near the boxing Theatre” and on 31st January 1784 he writes “No burial nor wedding this week. No trade for the Sexton”.

Not all the inhabitants of Oundle attended the parish Church. There was a flourishing congregation of independents, or as they were later known Congregationalists. They worshipped at the fine classical building known as the Upper or Great Meeting. The Great Meeting was rebuilt as the Congregational Church in 1864 and is now the Stahl Theatre. John Clifton's records occasional burials at the Upper Meeting, such that of Eleanor Wright, daughter of the minister who was buried there in October 1778. When the Chapel was converted to a Theatre in the 1970s, several skeletons were unearthed on the site. The year 1778 contains a number of entries referring to a serious outbreak of smallpox, in spite of the use of inoculation, to which John Clifton refers. There were hundreds of cases and many deaths. On April 25th 1778 he writes ”Another child of Mary Eden’s buried tonight from the workhouse. A child of Thomas Richardson's buried tonight, they both died of the smallpox”.

In 1766 John Clifton had been appointed to serve for a year as overseer of the poor, to administer poor relief, either to the people in their own home, or in the parish workhouse in West Street. The accounts of the 18th century overseers still survive in the County Record Office and show how the money was collected and how it was spent. The workhouse subsequently became the Victoria Inn after the Oundle Union Workhouse – which some of you, though not me, may remember - was built in 1836.

John Clifton was clearly a busy man occupied with his business and his civic responsibilities, but the various entries in his journals and the books listed in the codicil to his will show him engaged in leisure pursuits. He refers to sports such as cockfighting, bull running and watching what he described as “The best football match today in our 20 acres as ever I saw in my life” and enjoying an “Exhibition of fireworks at the new Bowling Green”.

He confesses to being among a party of gamblers in the churchyard and refers with apparent enjoyment to the fights which took place at the Ship, the Crown and even on the road just before his door. Other pastimes were more civilised. On two occasions travelling Theatre companies visited Oundle and performed in the area known as Crown Court. On 18th of January 1771, he writes “Tonight Mr Moor’s Company of Players opened a theatre down Mr Hawthorne's yard, and ‘Hamlet Prince of Denmark’ was the first play they acted and on 12th of March the play was ‘School for Raikes’ with the farce ‘The Rival Clowns’ or ‘Damon and Phillida’”.

John Clifton also owned a number of books, ranging from ‘Two Volumes of Highwaymen and Pirates’ to Homer’s ‘Iliad’ and including ‘The Complete Gardner’. He grew all kinds of vegetables and fruits including potatoes, runner beans, lettuce, cucumbers, and winter spinach, as well as apples and cherries All good practical crops. However, he also grew flowers, certainly for pleasure and perhaps for profit, and at the end of February 1776 records “A nice blow of snowdrops in my garden now and from a week past”.

There is so much more I could say but I thought I would end with a glimpse of the pleasures of 18th century gardening.

Julia Moss

28th July 1998

Acknowledgements

“Oundle in the Eighteenth Century” by Alice Osborne and David Parker 1994 Spiegl Press

The usual crops were wheat, peas and beans, and barley, and every third or fourth year a field would be kept fallow to rest it. The drawing shows sheep down on the meadows, still a familiar sight from Barnwell bridge. As the fields were farmed in common, there could be no farmhouses in the fields- the land was farmed from the town and John Clifton makes frequent reference to agricultural matters, for instance, in 1778 he wrote that “St Sythe’s Field and Pexley Field were wheat that year”. Pixley Field lay around Benefield Road, near the Golf Club and some of it is still agricultural land. Much of St. Sythe’s Field is occupied by the buildings and playing field of Prince William school.

On 22nd of August Clifton wrote “A very hot day - Mr. Chatteris’s harvest cart tonight. Old Tom Hawthorn’s harvest cart tonight. These are the first this year”. In those days harvest generally seems to have been later - probably the varieties of wheat used took longer to ripen. Crops were brought back from the fields in the harvest carts and stored in the backyards of the farmers’ houses in town - some of the grand houses like Cobthorn and The Berrystead had substantial stone barns which are still standing. For the farmers in West Street access to their backyards would have been from South Road and Milton Road, known as South Backside and North Backside respectively. Oundle’s first map or street plan, made in the early 19th century when the open fields were enclosed, shows the layout of the town with the long narrow strips behind the houses and gives the contemporary names such as Chapel End.

The getting in of the harvest was celebrated in the usual way. John Clifton's entry for 25th of August 1778 records “A glorious fine harvest day… Mrs Palmer’s Harvest Cart tonight and the fellows all drunk”. Harvest beer was apparently stronger the normal beer!

It's likely that most of these Oundle farmers were not just farmers, they probably had another occupation as well. The militia list of the previous year,1777, shows a few farmers and graziers but there were” innholders”, butchers, bakers, shoemakers, gardeners, wheelwrights and a fellmonger, as well as a man in more unusual occupation such as hairdresser, and the basket maker. Some at least of these must hold farmland in the open fields. Oundle formed part of the Manor of Biggin and the manorial court rolls contain much valuable information about property holding in the town. The militia list gives the occupation of a number of men as servants but few if any would have been indoor servants, such as footman, most of them would have been farm servants, or agricultural labourers.

Market towns like Oundle also provided a wide range of services to the surrounding villages, themselves agricultural settlements.

Although the street- plan of the town centre has changed little and some of the buildings such as the parish Church, Cobthorn, Bramston, The Berrystead, and even the Mill Lane cottages, remain externally much as they were in the 18th century, there have been important changes in the town's overall appearance, particularly in the marketplace. Some of you will be familiar with Shilibeer’s prints of the marketplace before the improvement act of 1825 and after. The improvements swept away the Butter Cross and the higgledy-piggledy collection of buildings known as Butcher’s Row and replaced them with the Market Hall. These prints present a much less tidy and orderly town centre and they also show clearly the cobbles and the lack of pavements.

In Clifton's day Oundle school was a small Grammar School and the school buildings, which now dominate the upper end of New Street, were not yet built in the early 18th century the only school building was the old guild hall, both almshouse and school room, which was replaced in the 1850s by Laxton Long Room.

The first of the school’s “new” buildings was the schoolmaster's house in 1763, which was built by Martin Cole of Peterborough, and entries in the day books suggest that John Clifton may have undertaken some of the carpentry. Houses which now form part of Oundle school such as Cobthorn, Bramston and the old water board were all privately owned, and John Clifton frequently refers to work which he undertook for the owners. For instance, on December 15th1766 he writes “Myself at Mr. Bramston's sash and blinds to the street parlour windows all day” and a few days later “Myself in the morning and till 2 o'clock hanging a Bell in Mr Bramston's nursery, then at Mr Johnston's houses taking an account of the stuff”.

He and his assistants were also involved in making coffins, sadly often for children, and in making furniture for various customers. He did a lot of work for Mr Burton who lived at Queen Anne’s. For example, in January 1772 he writes “Richard all day in the shop finishing Mr Burton's Oak table and beginning a mahogany 2 leaf Ditto for him”. The following years there were various entries relating to Mr Burton's bookcase “Richard at the cornice and frame to Mr Burton's bookcase”, entries like this and the codicil to John Clifton's own will listing all his possessions, give some idea of the household possessions of the day.

Alice Osborne did a great deal of work on the Oundle buildings of the time and she came to the conclusion, from entries in the day books and elsewhere, that John Clifton owned a number of properties in the town. She thinks he may have lived in Mill Lane as a boy, but as an adult he lived in West Street in a building part of which was occupied by one of Oundle's numerous pubs, the Green Man. In August 1778 he writes “The new sign post fixed by Mr Ashley's door today and the new sign of the “Green Man” hung in the frame on top of it”. In more recent times Mr Wade had a butcher’s shop in part of the building.

As I mentioned earlier John Clifton was a man of wide interest, who took a very active part in the life of the town, but there is one important aspect of life about which he had nothing to say - family life. He remained a bachelor and his view of his fellow townsmens’ marital affairs was often, though not invariably, rather cynical. In January 1779 he wrote “This morning my old neighbour nanny Eaton was married at our church to a young man of Geddington named Brown. Better late than never”.

There are many references to the parish church in Clifton's day books, relating mainly to the fabric rather than to the more spiritual aspects of the church life. In June 1766 he wrote ”Myself and William the church all day at the first bay of roofing at the South aisle with new beam, etc.” In January the following year he wrote “Myself at the church on the leads and at the bells. Shovelling snow away”. My impression is that the winters were colder than they are now. For instance, on the 14th of January 1768 he wrote “Tonight they broke the ice at Barnwell Bridge it having been a severe frost and deep snow ever since two days before Christmas”.

As a carpenter John Clifton was frequently employed in making coffins and it has been suggested he may have become Sexton after the death in 1772 of John Glasborow who had held the post for over 30 years. A very sad entry for 6th September 1776 reads “A little child of Mr Bishop's supervisor buried tonight near the boxing Theatre” and on 31st January 1784 he writes “No burial nor wedding this week. No trade for the Sexton”.

Not all the inhabitants of Oundle attended the parish Church. There was a flourishing congregation of independents, or as they were later known Congregationalists. They worshipped at the fine classical building known as the Upper or Great Meeting. The Great Meeting was rebuilt as the Congregational Church in 1864 and is now the Stahl Theatre. John Clifton's records occasional burials at the Upper Meeting, such that of Eleanor Wright, daughter of the minister who was buried there in October 1778. When the Chapel was converted to a Theatre in the 1970s, several skeletons were unearthed on the site. The year 1778 contains a number of entries referring to a serious outbreak of smallpox, in spite of the use of inoculation, to which John Clifton refers. There were hundreds of cases and many deaths. On April 25th 1778 he writes ”Another child of Mary Eden’s buried tonight from the workhouse. A child of Thomas Richardson's buried tonight, they both died of the smallpox”.

In 1766 John Clifton had been appointed to serve for a year as overseer of the poor, to administer poor relief, either to the people in their own home, or in the parish workhouse in West Street. The accounts of the 18th century overseers still survive in the County Record Office and show how the money was collected and how it was spent. The workhouse subsequently became the Victoria Inn after the Oundle Union Workhouse – which some of you, though not me, may remember - was built in 1836.

John Clifton was clearly a busy man occupied with his business and his civic responsibilities, but the various entries in his journals and the books listed in the codicil to his will show him engaged in leisure pursuits. He refers to sports such as cockfighting, bull running and watching what he described as “The best football match today in our 20 acres as ever I saw in my life” and enjoying an “Exhibition of fireworks at the new Bowling Green”.

He confesses to being among a party of gamblers in the churchyard and refers with apparent enjoyment to the fights which took place at the Ship, the Crown and even on the road just before his door. Other pastimes were more civilised. On two occasions travelling Theatre companies visited Oundle and performed in the area known as Crown Court. On 18th of January 1771, he writes “Tonight Mr Moor’s Company of Players opened a theatre down Mr Hawthorne's yard, and ‘Hamlet Prince of Denmark’ was the first play they acted and on 12th of March the play was ‘School for Raikes’ with the farce ‘The Rival Clowns’ or ‘Damon and Phillida’”.

John Clifton also owned a number of books, ranging from ‘Two Volumes of Highwaymen and Pirates’ to Homer’s ‘Iliad’ and including ‘The Complete Gardner’. He grew all kinds of vegetables and fruits including potatoes, runner beans, lettuce, cucumbers, and winter spinach, as well as apples and cherries All good practical crops. However, he also grew flowers, certainly for pleasure and perhaps for profit, and at the end of February 1776 records “A nice blow of snowdrops in my garden now and from a week past”.

There is so much more I could say but I thought I would end with a glimpse of the pleasures of 18th century gardening.

Julia Moss

28th July 1998

Acknowledgements

“Oundle in the Eighteenth Century” by Alice Osborne and David Parker 1994 Spiegl Press